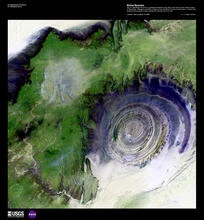

Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara) - Mauritania

Location and Appearance

The Richat Structure is located in the Adrar Plateau of the Sahara Desert, near Ouadane in Mauritania. Its distinctive concentric rings, resembling a giant bullseye, make it highly visible from space, earning it the nickname "Eye of the Sahara." This feature has captivated astronauts since the early days of space exploration.

The Richat Structure, also known as the Eye of the Sahara, is a remarkable geological formation in Mauritania’s Adrar Plateau, near Ouadane. Spanning 40 kilometers (25 miles) in diameter, this circular structure features concentric rings of ancient rocks, visible from space, making it a standout feature in the Sahara Desert. Unlike early assumptions of an impact crater origin, research reveals it as an eroded geological dome, shaped by igneous intrusion and millions of years of erosion. Recognized by the International Union of Geological Sciences as a top geological heritage site, the Richat Structure offers a fascinating glimpse into Earth’s deep geological history.

What Is the Richat Structure Geologically?

The Richat Structure, located in the Adrar Plateau of Mauritania’s Sahara Desert, is a 40-kilometer-wide geological dome, not an impact crater as once thought. Its bullseye-like concentric rings, formed by a complex interplay of igneous activity and erosion, span rocks from 600 million years old to the Cretaceous period. First observed from space in 1965 during the Gemini IV mission, it has been extensively studied, earning recognition by the International Union of Geological Sciences as one of 100 geological heritage sites. Research from the 1950s to 2021, including key findings in 2005 and 2008, clarified its origins, correcting earlier errors like mistaking coesite for barite. Its unique geology provides valuable insights into magmatic processes, erosion in desert environments, and Earth’s geological evolution.

How Did the Richat Structure Form?

The Richat Structure’s formation began during the Cretaceous period, roughly 100 million years ago, with a subsurface igneous intrusion that uplifted the overlying sedimentary layers. This uplift created a dome, which wind and water erosion sculpted over millions of years into the concentric rings seen today. Early theories, sparked by its circular shape observed from space in the 1960s, suggested an impact crater origin, but studies starting in the 1950s debunked this, finding no evidence of shock metamorphism. Instead, its geology points to a terrestrial process, confirmed by modern aeromagnetic and gravimetric mapping.

The structure’s slightly elliptical shape reflects differential erosion, where resistant layers like quartzite formed high-relief cuestas, while softer materials eroded away. A central siliceous breccia, spanning 30 kilometers and dated to 98.2 ± 2.6 million years ago using 40Ar/39Ar methods, highlights hydrothermal alteration tied to the original igneous event. This process distinguishes the Richat Structure as a "spectacular magmatic concentric alkaline complex."

Geological Composition: What Rocks Make Up the Richat Structure?

The Richat Structure in Mauritania is a geological mosaic, blending sedimentary and igneous rocks that tell a story spanning 600 million years. Its concentric rings and central core contain a diverse array of rock types, each contributing to its unique formation:

| Rock Type | Description | Age/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Limestone-Dolomite | Forms the central core with a siliceous mega-breccia | Key to the structure’s heart |

| Basaltic (Gabbroic) | Ring dikes linked to a large magmatic body | Evidence of volcanic activity |

| Kimberlitic | Igneous intrusions within the structure | Dated to ~99 million years old |

| Alkaline Volcanic | Contributes to the dome’s formation | Part of the magmatic complex |

| Carbonatitic | Magmatic rocks cutting through other layers | 85 ± 5 Ma and 99 ± 5 Ma |

| Tholeiitic Suite | Bimodal rock layers intersected by others | Shows complex magmatic history |

| Proterozoic-Lower Paleozoic Strata | Concentric ridges of sedimentary rock | Up to 600 million years old |

Sedimentary layers, dipping outward at 10–20 degrees, range from Late Proterozoic sandstone at the center to Ordovician strata at the edges. Igneous rocks like gabbros, rhyolites, and kimberlites, alongside a central megabreccia, reflect the intense magmatic activity that shaped this dome. The interplay of these rocks and erosion crafted the Richat Structure’s iconic appearance.

Archaeology of the Richat Structure

The Richat Structure, located in the Adrar Plateau of Mauritania’s Sahara Desert near Ouadane, is not only a geological wonder but also a significant archaeological site. Known as the Eye of the Sahara, its 40-kilometer expanse has yielded evidence of human activity spanning hundreds of thousands of years. The structure’s prominence as a navigational landmark in the vast desert likely drew ancient peoples to its surroundings, leaving behind traces of their lives in the form of stone tools and potential encampments. These findings offer a window into prehistoric human adaptation and mobility in a region that was once far more hospitable than today’s arid landscape.

Key Archaeological Discoveries

The most notable archaeological evidence from the Richat Structure consists of Acheulean stone tools, which indicate a prolonged human presence in the area. These artifacts, found scattered across the structure’s outer rings and nearby wadis (dry riverbeds), provide critical insights into the lives of early humans in the Sahara:

- Acheulean Tools: Exceptional concentrations of handaxes, cleavers, scrapers, and other implements have been documented. The Acheulean industry, associated with Homo erectus and early Homo sapiens, spans from approximately 1.76 million to 130,000 years ago. These tools, typically made from local materials like quartzite (abundant in the structure’s eroded layers), suggest skilled craftsmanship and resource use.

- Distribution: The tools are primarily surface finds, concentrated along the outer concentric rings and in adjacent wadis. This pattern hints at temporary encampments, resource-gathering sites, or transit points, possibly linked to water sources or raw material availability during wetter climatic phases.

- Chronology: While precise dating is challenging due to the lack of stratified deposits in the desert environment, the tools’ typology aligns with Acheulean traditions across North Africa, placing them in the Middle Pleistocene (roughly 781,000 to 126,000 years ago). Some tools may date closer to the industry’s later phases, around 130,000 years ago.

Context and Environmental Conditions

The presence of Acheulean artifacts around the Richat Structure points to a time when the Sahara was a vastly different environment. During the "Green Sahara" periods—intermittent wet phases driven by shifts in monsoon patterns—the region supported savanna-like conditions with lakes, rivers, and vegetation. These conditions, occurring multiple times between 1.8 million and 10,000 years ago, would have made the area habitable for early humans:

- Paleoenvironment: Archaeological evidence aligns with paleoclimatic data suggesting that the Adrar Plateau, including the Richat Structure’s vicinity, once hosted water sources and flora. This environment likely attracted hunter-gatherers who exploited local resources, such as quartzite from the structure’s sedimentary layers, to craft tools.

- Human Adaptation: The tools indicate that early humans adapted to this landscape, possibly using the structure’s elevated rings or nearby wadis as strategic points for hunting, tool-making, or shelter. The lack of permanent settlement evidence suggests a nomadic or seasonal presence.

Historical Role as a Navigational Landmark

The Richat Structure, spanning a 40-kilometer diameter and characterized by its distinctive concentric rings, likely played a significant historical role as a navigational landmark within the vast expanse of the Sahara Desert. Its prominent visibility from great distances would have made it a natural beacon for ancient peoples traversing the challenging terrain, aiding in orientation and wayfinding. During earlier, wetter climatic periods when the Sahara was a savanna rather= rather than a desert, the structure may have served as a critical waypoint along migration paths or trade routes linking various North African populations. The presence of Acheulean tools, associated with early human activity, marks an initial chapter in its archaeological significance, suggesting its use dates back to prehistoric times. Its utility as a navigational aid likely persisted across multiple eras, potentially extending into later prehistoric periods. However, direct evidence of sustained occupation within its immediate vicinity during the Neolithic period (10,000–3,000 BCE) or subsequent historic eras remains scarce, leaving its long-term role as a landmark speculative but plausible given its striking and enduring physical presence.

Cultural Connections

The Richat Structure’s archaeological findings underscore its deep cultural significance, particularly for modern Mauritanian communities, including nomadic tribes, weaving it into their historical and cultural fabric. Locally known as Guelb er Richât (heart of Richat) or tagense (leather pouch opening) in Hassaniya Arabic, the structure is embedded in oral traditions and folklore as a powerful symbol of resilience and endurance. These names, while reflective of relatively recent cultural interpretations, may hint at a much older, enduring human connection to the site, potentially stretching back to its prehistoric utilization as a navigational or communal landmark. The discovery of ancient tools, such as those from the Acheulean period, indicates that the structure’s prominence as a distinctive feature in the landscape began millennia ago, establishing a foundational role that has evolved over time. This legacy of significance continues to resonate today, bridging ancient history with its ongoing cultural prominence among local populations, who maintain a living relationship with this extraordinary geological formation.

Significance of the Archaeological Record

The archaeological record of the Richat Structure provides critical insights into both human history and environmental transformations, enriching our understanding of the region’s past. The presence of Acheulean tools aligns with evidence of a "Green Sahara," a period when wetter conditions transformed the now-arid landscape into a habitable savanna. This paleoenvironmental clue highlights how climate shifts influenced human occupation, with the tools indicating that the area supported viable living conditions during these lush phases, in stark contrast to its present desert state. Furthermore, the distribution and typology of these tools connect the Richat Structure to a wider network of Acheulean sites spanning North Africa, from the Maghreb in the north to the Sahel in the south. This suggests that the structure was integrated into ancient migration routes or resource corridors, playing a role in the broader patterns of early human mobility across the continent. Despite its significance, research remains limited, with most findings derived from surface collections due to the structure’s remote location and the lack of systematic excavation. The potential for subsurface exploration is substantial—undisturbed deposits could yield detailed evidence of tool-making workshops, temporary camps, or even organic remains preserved by the desert’s arid conditions, offering a deeper glimpse into prehistoric life and activities at this remarkable site.

Limitations and Future Exploration

Despite its archaeological richness, the Richat Structure’s record has gaps:

- Limited Excavation: The harsh desert environment and logistical challenges have restricted in-depth digs. Surface scatters dominate the evidence, leaving questions about deeper layers or more permanent human traces unanswered.

- Later Periods: While the broader Adrar region shows Neolithic activity (e.g., rock art, pottery), the structure’s immediate vicinity lacks clear evidence of occupation after the Acheulean period, possibly due to increasing aridity. This gap suggests a shift in human focus as the Sahara dried.

- Speculative Theories: Some propose the structure as the site of Atlantis, citing its circular shape and ancient human presence. However, the Acheulean tools and absence of monumental structures refute this, aligning instead with a nomadic hunter-gatherer past.

Conclusion: A Prehistoric Legacy

The archaeology of the Richat Structure near Ouadane, Mauritania, underscores its role as more than a geological marvel. Acheulean stone tools, dating back over a million years, reveal a prehistoric human presence tied to a once-green Sahara. As a navigational landmark and resource hub, it shaped early human activity, leaving a legacy echoed in modern Mauritanian folklore. Though excavation remains limited, these findings illuminate ancient adaptation and mobility, making the Eye of the Sahara a vital piece of humanity’s deep past.

The Atlantis Hypothesis

The idea that the Richat Structure could be the site of Atlantis stems from Plato’s dialogues, Timaeus and Critias, where he describes a highly advanced civilization destroyed by a cataclysmic event around 9,000 years before his time (approximately 11,600 years ago). Plato’s Atlantis is depicted as a concentric city with rings of water and land, located beyond the "Pillars of Hercules" (commonly interpreted as the Strait of Gibraltar) and associated with a vast plain and towering mountains.

Proponents of the Richat Structure as Atlantis, popularized by figures like Jimmy Corsetti in his 2021 documentary Visiting Atlantis, point to several intriguing parallels:

- Concentric Rings: The Richat Structure’s natural rings of ridges and eroded valleys bear a striking resemblance to Plato’s description of Atlantis’s layout—alternating rings of water and land surrounding a central island.

- Geographical Context: While the Richat Structure is now in the desert, evidence suggests the Sahara was once a lush, fertile region with rivers, lakes, and vegetation as recently as 5,000–10,000 years ago, aligning with Plato’s timeline. The adjacent Adrar Plateau could represent the "high mountains" he mentioned, and the surrounding flatlands might correspond to the "great plain."

- Size Correspondence: Plato describes Atlantis’s central plain as 2,000 by 3,000 stadia (roughly 370 x 555 kilometers). The Richat Structure itself is smaller, but the surrounding region could fit this description if interpreted generously.

- Cataclysmic Destruction: Some hypothesize that a massive flood or tectonic event could have submerged or altered the region, leaving the Richat Structure as a remnant of a once-thriving hub.

Supporting Evidence and Speculation

- Paleoenvironmental Data: Studies of ancient climate patterns indicate that the Sahara experienced a "Green Sahara" phase during the Neolithic Subpluvial (circa 9000–5000 BCE), with evidence of human settlement, fauna, and waterways. Rock art in the region depicts animals like giraffes and crocodiles, suggesting a wetter past.

- Archaeological Traces: Limited excavations near the Richat Structure have uncovered Stone Age artifacts, such as arrowheads and pottery, hinting at human presence. However, no definitive evidence of an advanced civilization matching Plato’s description has been found.

- Location Beyond the Pillars: If the "Pillars of Hercules" refer to the Strait of Gibraltar, the Richat Structure lies in northwest Africa, plausibly "beyond" this point from a Greek perspective.

Counterarguments and Scientific Skepticism

Despite its allure, the Atlantis hypothesis faces significant challenges:

- Geological Timeline: The Richat Structure’s formation predates human civilization by tens of millions of years, and its current shape results from erosion, not a sudden disaster. No evidence supports a cataclysmic flooding event in the region within human history.

- Lack of Urban Evidence: Plato’s Atlantis was a sophisticated city with temples, canals, and harbors. Archaeological surveys of the Richat Structure have not revealed structures, metallurgy, or other signs of an advanced society.

- Location Discrepancy: Many scholars argue Atlantis, if real, was more likely in the Mediterranean (e.g., Santorini or Crete), not the Sahara. The Richat Structure’s inland desert position contradicts Plato’s emphasis on a maritime civilization.

- Myth vs. Reality: Most historians consider Atlantis a philosophical allegory rather than a historical place, crafted by Plato to illustrate moral and political ideas.

Cultural and Modern Interest

The Richat Structure’s connection to Atlantis has gained traction in popular culture, fueled by satellite imagery and online discussions. Its otherworldly appearance has inspired explorers, conspiracy theorists, and even tourism to Mauritania, though the site remains remote and largely unstudied. Advances in remote sensing and archaeology could one day shed more light on its human history, but for now, the link to Atlantis remains speculative.